Using eye-tracking to test the theory of mind and social learning in great apes and children

Eye-tracking is a potent technique for testing the social cognition of non-verbal subjects, including great apes and human infants. In this project, I propose two eye-tracking studies aimed at understanding the theory of mind skills (the ability to comprehend others' minds) and social learning abilities in great apes and children.

In one study, I address the recent replication issue with the well-known anticipatory-looking false-belief task in human subjects. Originally devised by Southgate et al. (2007) to test human infants aged 1–2 years, this task examines whether participants can anticipate an agent's goal based on the agent's belief, even when that belief contradicts reality (false belief). The results have since been replicated across laboratories and in nonhuman primates, including great apes (Kano et al., 2019; Krupenye et al., 2016) and monkeys (Hayashi et al., 2020). Oddly, however, recent studies have reported failures to replicate with human adults and children, and even with young infants within the same age range as those in the original studies (Kulke & Rakoczy, 2018). These discrepancies suggest nuanced reasons for such non-replications. From my perspective, the issue likely lies in the storytelling aspect (how effectively the complex story is conveyed in the video). To address this, I am developing a new video stimulus to improve this aspect, with the aim of testing replication in human infants/children and adults.

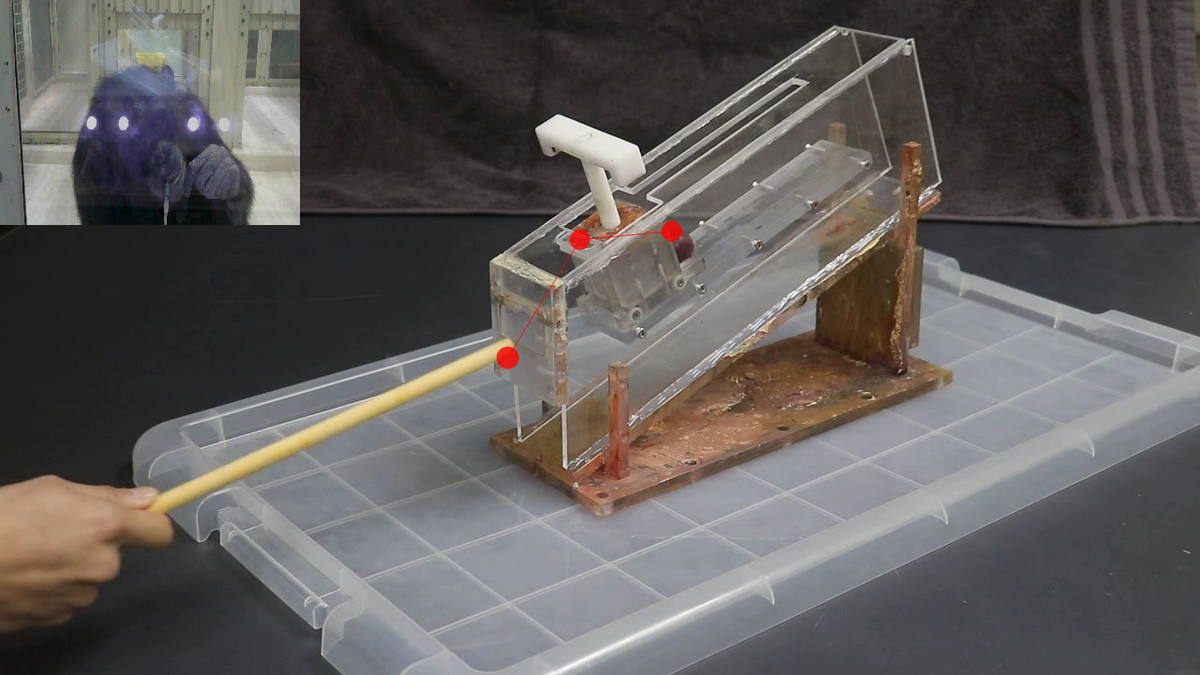

In another study, I examine how attention modulates social learning in great apes. In the field of animal culture research, a dominant view posits that human children "imitate" (showing a bias towards learning from the actions or manners of a demonstration), whereas nonhuman animals "emulate" (showing a bias towards learning from the outcomes of a device or the goals of a demonstration). However, recent studies suggest that this dichotomy may not hold true (Whiten, 2022). One aspect that is particularly understudied, especially in nonhuman animals, concerns attention: specifically, where they direct their attention during a demonstration while they are socially learning. Obtaining this knowledge is crucial for understanding how they encode social information during observation. In this study, I therefore test both great apes and human children using a well-known two-action task devised to test chimpanzees. In this task, they first watch a conspecific demonstrator solve the task using one of two actions in a video, and afterwards, they have the opportunity to solve the task themselves. I measure where they looked in the video and how their eye movement patterns predict their action-copying performance. I anticipate that the eye movement patterns of children and apes will generally be similar, though in specific contexts where a task-irrelevant action is observed (Horner & Whiten, 2005), apes might pay less attention to such actions than children (if apes are more biased towards "emulation").

References:

Hayashi, T., Akikawa, R., Kawasaki, K., Egawa, J., Minamimoto, T., Kobayashi, K., Kato, S., Hori, Y., Nagai, Y., Iijima, A., Someya, T., & Hasegawa, I. (2020). Macaques exhibit implicit gaze bias anticipating others’ false-belief-driven actions via medial prefrontal cortex. Cell Reports, 30(13), 4433-4444. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.013

Horner, V., & Whiten, A. (2005). Causal knowledge and imitation/emulation switching in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and children (Homo sapiens). Animal Cognition, 8(3), 164-181.

Kano, F., Krupenye, C., Hirata, S., Tomonaga, M., & Call, J. (2019). Great apes use self-experience to anticipate an agent’s action in a false-belief test. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(42), 20904-20909. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910095116

Krupenye, C., Kano, F., Hirata, S., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2016). Great apes anticipate that other individuals will act according to false beliefs. Science, 354(6308), 110-114. doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8110

Kulke, L., & Rakoczy, H. (2018). Implicit Theory of Mind – An overview of current replications and non-replications. Data in Brief, 16, 101-104. doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.11.016

Southgate, V., Senju, A., & Csibra, G. (2007). Action anticipation through attribution of false belief by 2-year-olds. Psychological Science, 18(7), 587-592. doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01944.x

Whiten, A. (2022). Blind alleys and fruitful pathways in the comparative study of cultural cognition. Physics of Life Reviews, 43, 211-238. doi.org

doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2022.10.003

Whiten, A., Horner, V., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2005). Conformity to cultural norms of tool use in chimpanzees. Nature, 437(7059), 737-740. doi.org/10.1038/nature04047